Rayleigh–Jeans law

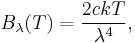

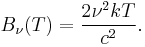

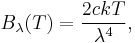

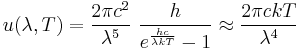

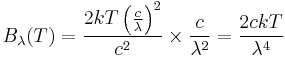

In physics, the Rayleigh–Jeans law attempts to describe the spectral radiance of electromagnetic radiation at all wavelengths from a black body at a given temperature through classical arguments. For wavelength λ, it is:

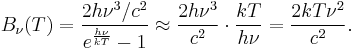

where c is the speed of light, k is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature in kelvins. For frequency ν, the expression is instead

The Rayleigh–Jeans law agrees with experimental results at large wavelengths (or, equivalently, low frequencies) but strongly disagrees at short wavelengths (or high frequencies). This inconsistency between observations and the predictions of classical physics is commonly known as the ultraviolet catastrophe,[1][2] and its resolution was a foundational aspect of the development of quantum mechanics in the early 20th century.

Contents |

Historical development

In 1900, the British physicist Lord Rayleigh derived the λ−4 dependence of the Rayleigh–Jeans law based on classical physical arguments.[3] A more complete derivation, which included the proportionality constant, was presented by Rayleigh and Sir James Jeans in 1905. The Rayleigh–Jeans law revealed an important error in physics theory of the time. The law predicted an energy output that diverges towards infinity as wavelength approaches zero (as frequency tends to infinity) and measurements of energy output at short wavelengths disagreed with this prediction.

Comparison to Planck's law

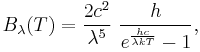

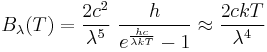

In 1900 Max Planck empirically obtained an expression for blackbody radiation expressed in terms of wavelength λ = c/ν:

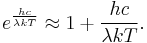

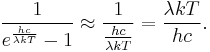

where h is the Planck constant. The Planck law does not suffer from an ultraviolet catastrophe, and agrees well with the experimental data, but its full significance (which ultimately led to quantum theory) was only appreciated several years later. In the limit of very high temperatures or long wavelengths, the term in the exponential becomes small, and so the exponential is well approximated by its first-order Taylor polynomial:

Then

This results in Planck's blackbody formula reducing to

which is identical to the classically derived Rayleigh–Jeans expression.

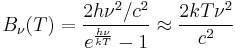

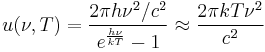

The same argument can be applied to the Blackbody Radiation expressed in terms of frequency ν = c/λ in the limit of small frequency:

This last expression is the Rayleigh–Jeans law in the limit of small frequency.

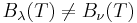

Consistency of frequency and wavelength dependent expressions

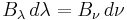

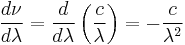

When comparing the frequency and wavelength dependent expressions of the Rayleigh–Jeans law it is important to remember that

because  has units of energy emitted per unit time per unit area of emitting surface, per unit solid angle, per unit wavelength, whereas

has units of energy emitted per unit time per unit area of emitting surface, per unit solid angle, per unit wavelength, whereas  has units of energy emitted per unit time per unit area of emitting surface, per unit solid angle, per unit frequency. To be consistent, we must use the equality

has units of energy emitted per unit time per unit area of emitting surface, per unit solid angle, per unit frequency. To be consistent, we must use the equality

where both sides now have units of energy emitted per unit time per unit area of emitting surface, per unit solid angle.

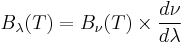

Starting with the Rayleigh–Jeans law in terms of wavelength we get

where

.

.

This leads us to find:

.

.

Other forms of Rayleigh–Jeans law

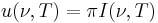

Depending on the application, the Planck Function can be expressed in 3 different forms. The first involves energy emitted per unit time per unit area of emitting surface, per unit solid angle, per unit frequency. In this form, the Planck Function and associated Rayleigh–Jeans limits are given by

or

Alternatively, Planck's law can be written as an expression  for emitted power integrated over all solid angles. In this form, the Planck Function and associated Rayleigh–Jeans limits are given by

for emitted power integrated over all solid angles. In this form, the Planck Function and associated Rayleigh–Jeans limits are given by

or

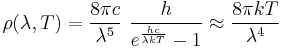

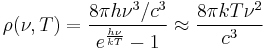

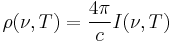

In other cases, Planck's Law is written as  for energy per unit volume (energy density). In this form, the Planck Function and associated Rayleigh–Jeans limits are given by

for energy per unit volume (energy density). In this form, the Planck Function and associated Rayleigh–Jeans limits are given by

or

See also

References

- ^ Astronomy: A Physical Perspective, Mark L. Kutner pp. 15

- ^ Radiative Processes in Astrophysics, Rybicki and Lightman pp. 20–28

- ^ Astronomy: A Physical Perspective, Mark L. Kutner pp. 15